This is the text of a talk I gave at New York City DSA’s night school, Socialists of NYC series, May 14, 2024

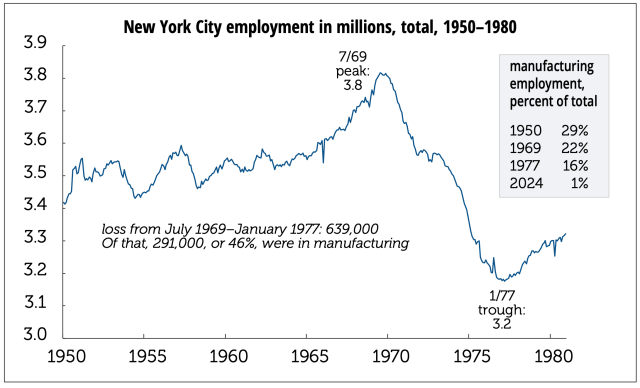

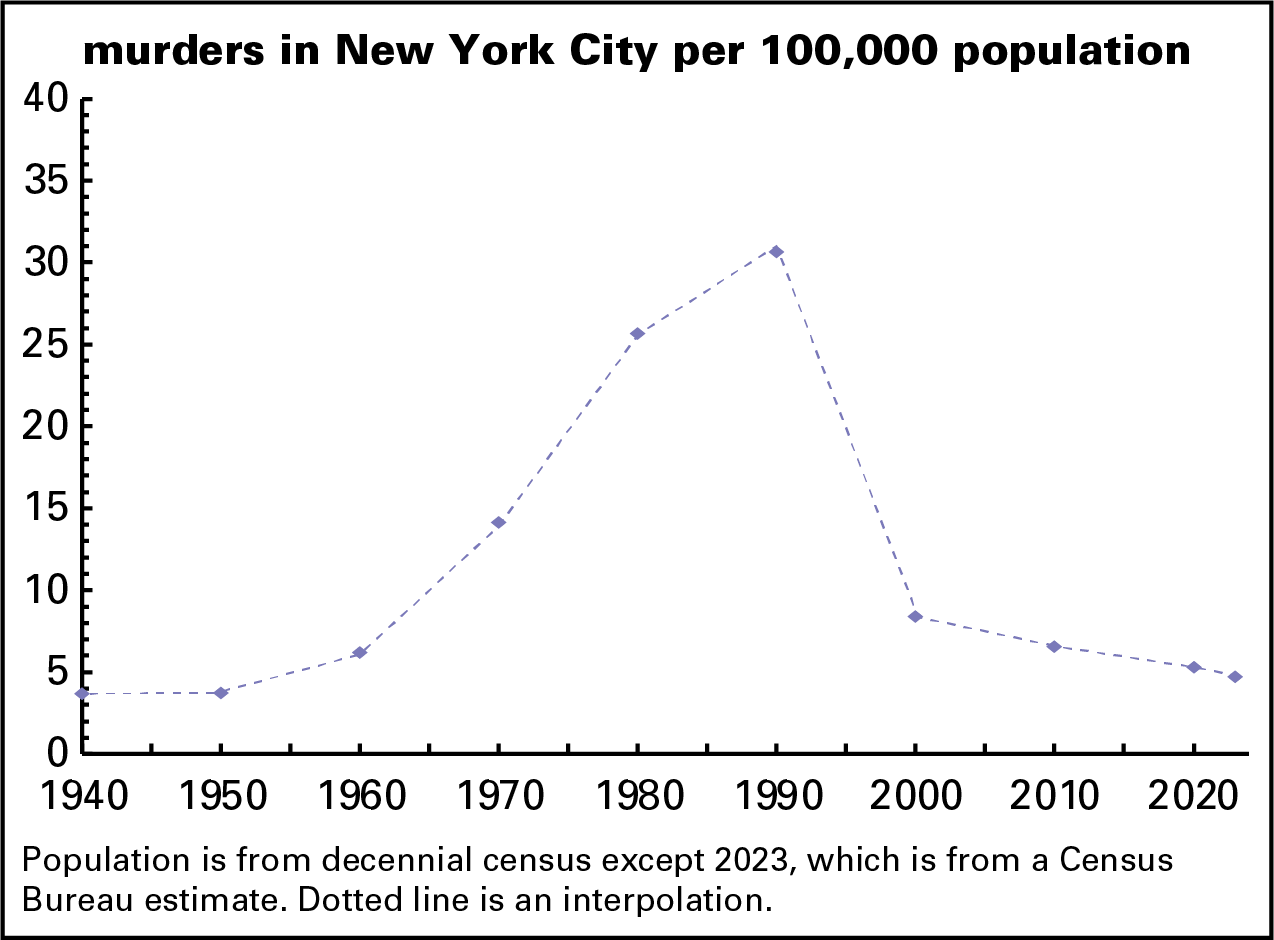

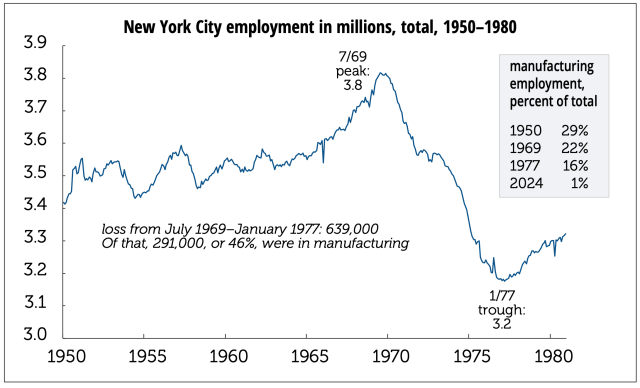

As the 1960s were turning into the 1970s, New York City was coming off a long economic boom. Sure, we’d lost 151,000 manufacturing jobs between 1950 and the 1969 peak, but that was almost exactly offset by a gain in finance, and overall employment in the city was up 391,000. There were signs of budgetary trouble starting in the mid-1960s, but those issues were patched over with a combination of tax increases, fiscal trickery, and wishful thinking.

There was a recession in 1970, which was felt here, but by 1971 the rest of the country was recovering. Not New York City, though; we continued to lose jobs. During the 1971–1973 economic expansion, the US increased employment by 15%, but in New York City, it fell 4%. Half that loss was in manufacturing—one in ten factory jobs disappeared in just those three years—even though national manufacturing employment rose briskly. The city’s manufacturing firms were mostly small, and squeezed by high rents, taxes, and wages.

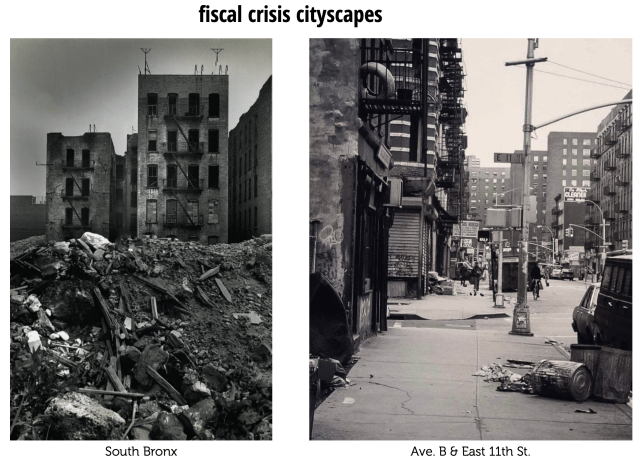

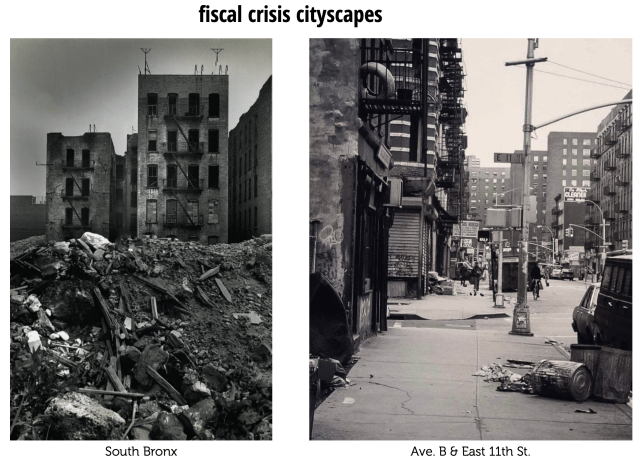

And then the deep recession of 1974–1975 hit—then the worst since the 1930s. We lost another 6% of our jobs, three times the national rate, again with about half coming from manufacturing. Between 1965 and 1974, 200,000 housing units were abandoned and tax delinquencies rose sharply. The number of people on some form of public assistance had nearly tripled from 1960, from just over 300,000 to 1.3 million, an eighth of the population. Containerization helped doom the city’s ports, as maritime activity moved over to New Jersey, killing port jobs and industrial jobs dependent on the port. On top of tax receipts being driven lower by economic decay, Nixon was hacking away at the revenue sharing programs that financed a lot of the growth in social spending in the 1960s. A hefty set of troubles, but the city borrowed its way through them.

And then in May 1975, the banks cut us off. What had been a medium-slow bleed turned into a hemorrhagic crisis.

portents of crisis

There were plenty of early portents of what was to come. In December 1973, a big chunk of the West Side Highway fell down, a visible symbol of creeping rot. In April 1974, Con Ed skipped its dividend for the first time since it began paying one in 1885; the money just wasn’t flowing in from a troubled economy like it used to.

And there were hints of where it all would go. On taking office as governor of New York in January 1975, months before the formal onset of the fiscal crisis, Hugh Carey declared “the days of wine and roses are over…we must all live by a rule of austerity for as far ahead as we can see.” A month later, the Urban Development Corporation, an entity created by the grandiose brain of a Carey predecessor, Nelson Rockefeller, to promote urban renewal and high-rise housing—Roosevelt Island was its masterpiece—defaulted on its debt.

Fiscal crises were fairly common in the city’s history. A decade before the big one, the new Lindsay administration, threatened by a serious flow of red ink, appointed a Temporary Commission on City Finances in 1966. In a sharp contrast with what would emerge a decade later, the commission recommended tax increases and more federal aid. “Doubtless there is…some waste. But the basic fact is that civilization has to be paid for,” it concluded. A personal income tax was introduced, business taxes were increased, and the city began charging its own sales tax.

As Michael Reagan points out in his dissertation on the 1975 crisis, Wall Street responded to this mini-crisis in a surprisingly mellow way. For example, in a research note, the predecessor of Citibank wrote “Local government, for its part, needs to concentrate on maintaining, and even increasing, services required by the people….” Over the next few years, though, Citi’s tone changed, and by the end of the decade, it expressed increasing worry about welfare and the various moral and occupational deficits among the poor. The broader discourse shifted from structural problems generating poverty to embracing the culture of poverty theory that the poor suffered profound defects of character and mental acuity.

Bankers had consented to the fiscal trickery for years and made lots of money from it. Whenever there’s a debt crisis, capital’s pundits blame the irresponsibility of the borrowers; the irresponsibility of the lenders always gets a pass. But nothing is forever. The bankers had enough, and as soon came clear, they held all the cards.

how’d we get there?

It was nice while it lasted. Though it’s probably an exaggeration to say New Yorkers enjoyed a kind of social democracy in one city, it’s not completely wrong.

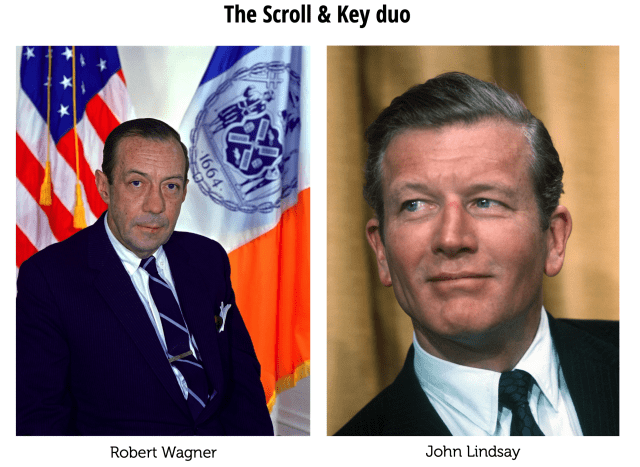

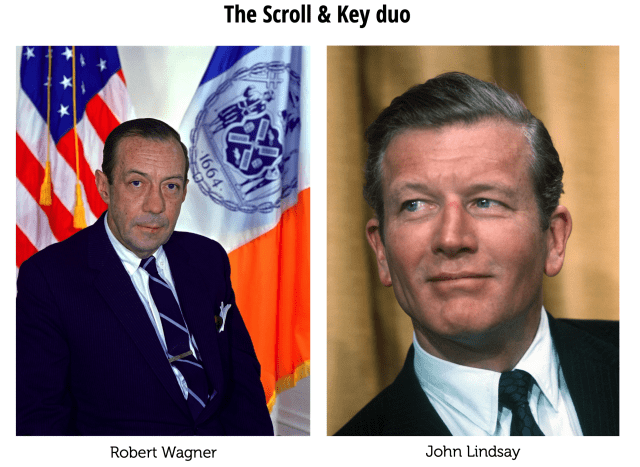

It’s tempting to think of the mayoralty of Robert Wagner, which ran for three terms, 1954–1965, the period of the city’s ambitious extension of the New Deal, as something of a Golden Age. Though things started showing signs of wear, for most of Wagner’s term the city was prosperous and spent freely. The housing stock increased by 18%, over 40% of it from the public sector, including public housing for the poor and the Mitchell-Lama program for middle-income households. Overcrowding fell by half. Wagner recognized city unions and instituted collective bargaining. Money looked plentiful—though Wagner started borrowing to pay expenses toward the end of his term.

Borrowing was encouraged by fiscal pressures coming from the changing city population. Better-off whites, terrified by the arrival of poor black migrants from the South and Puerto Ricans from the island, moved to the tax-sheltered suburbs. Manufacturing’s decline, which would grind on for decades, was already underway. Both these developments hammered revenues. At the same time, with the increase in poverty, there was unrelenting pressure for increased social spending.

The relative peace of the Golden Age came to an end as well, as black and brown New Yorkers, tired of segregation, poverty, and bad housing, got more militant, and some white people weren’t happy about that. Anger at the police rose too. In July 1964, in response to a cop killing a 15-year-old, people in Harlem and Bed-Stuy rioted for nearly a week. Starting around 1960, crime began its decade long rise. Divisions of all kinds sharpened.

In 1966, the uber-WASPy John Lindsay took over from Wagner. Curiously, both went to elite private schools and Yale, where they were members of the same secret society (Scroll & Key).

But, in contrast to the un-slick hereditary pol, Lindsay came off as a patrician, a symbol of a new social order. As Kim Phillips-Fein puts it in her book Fear City, “he was a leader for the postindustial town to come,” a break with the working-class past. (I saw him in a bathing suit on a beach in the Hamptons in the mid-1970s throwing around a football. He was well into his 50s and he looked fabulous.) Alas, plans for the postindustrial city were complicated by an exodus of corporate headquarters to the suburbs and beyond.

Lindsay was supposed to calm racial tensions and mitigate black and brown poverty—he was even seen as having run against the police. Things didn’t work out as planned. Five hours into Lindsay’s mayoralty, the Transport Workers, led by the fierce class warrior Mike Quill, went out on strike. (Quill died three days after the strike was settled.) That set the tone for Lindsay’s reign, one of frank social conflict across classes and races and constant pressure on the city budget to calm the tensions with new programs. The welfare rights movement was founded just months after his inauguration, was very active in the city, and it was quite effective in its early years. The Black Panthers and the Young Lords were at their peak during the Lindsay era, greatly upsetting the bourgeoisie and white middle class.

Fiscal problems haunted Lindsay. On taking office, he was so alarmed by the state of the city’s finances that he pronounced himself a “receiver in bankruptcy.” The tax increases recommended by the Temporary Commission on City Finances, which I mentioned above, plus a stronger economy, and a shower of Great Society money from Washington, righted the budget for a few years. But by 1970 the red ink was back.

(A curious class footnote: the patrician Lindsay never liked unions much. During a garbage strike, he suggested to Gov. Rockefeller that the National Guard break the strike; Rockefeller said no, that would look too 19th century, meaning, one assumes, the sort of thing done by his ancestors.)

Lindsay was succeeded in 1974 by Abraham Beame, who’d served previously as city comptroller. He ran on his budget expertise, which consisted mainly, sad to say, of knowing how to borrow his way out of the deficits he couldn’t hide with creative accounting.

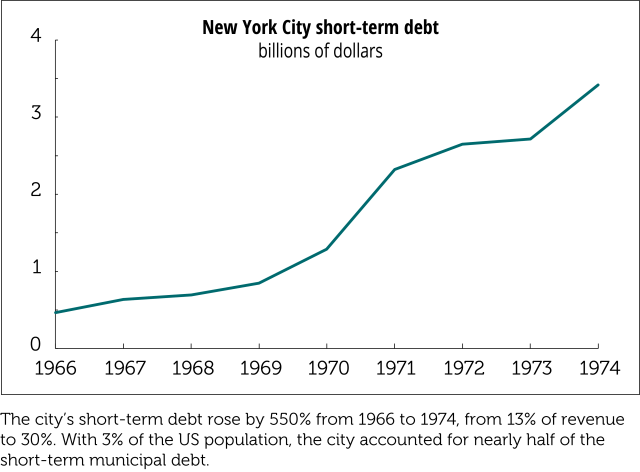

The city did lots of short-term borrowing. With 3% of the population, it accounted for nearly half the short-term municipal debt in the US. As comptroller, Beame had shortened the average maturity of the city’s debt, something he inexplicably bragged about. Much of that short-term borrowing went to finance long-term obligations like the mortgages that funded the Mitchell-Lama housing program. At the state level, you could say the same about the Urban Development Corporation.

It’s a rule of orthodox finance, and a largely correct one, that you should borrow over a period of time that’s relevant to the project. If you, the city, need to pay some bills now but you won’t be getting paid for a few months, it makes sense to borrow short; you can pay off the debt when the money comes in. If you’re financing a mortgage, which will be paid off over decades, you should borrow long-term. The reason is that the interest rate on the mortgage is fixed, say at 7%. If you borrow long-term at 5%, you’re guaranteed a profit. Short-term rates are generally lower than long-term, which makes them tempting. So instead of borrowing at 5%, you borrow at 4% maybe—which is nice unless interest rates rise to 8%, turning the mortgage into a loss-maker—which is what happened as interest rates rose from the mid-60s into the mid-70s. That, and when you borrow short-term, you have to go back to your lenders constantly, and they can get whimsical in their demands.

As James O’Connor put it in The Fiscal Crisis of the State, debt tightens capital’s grip on the state. When capitalists borrow to expand, he argued, they can invest the proceeds and make a higher return than they have to pay in interest. The public sector, however, mostly spends on projects that don’t pay direct returns. The bond market had the state in its grip, and New York City’s bankers soon tigthened it.

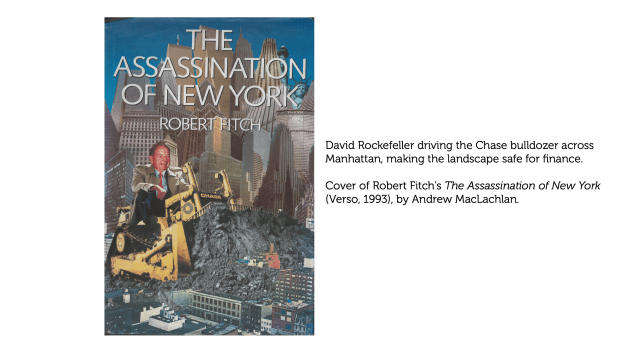

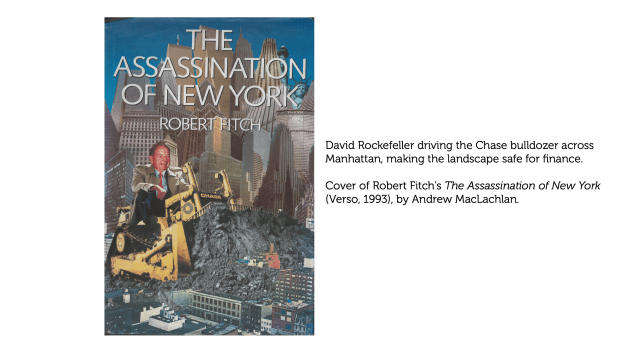

Fitch: planned deindustrialization

This is a good time to file a dissent with my earlier comments about how manufacturing was driven out of town because of high wages and taxes. My late friend Robert Fitch, author of The Assassination of New York (which Verso sadly let go out of print), argued that the exodus was engineered by the planning cabal, a consortium made up of big real estate, their think tanks (like the Regional Plan Association, the RPA), foundations (like the Rockefeller Brothers Fund—Rockefellers are all over this), and their servants in city government. Here’s a look at its cover, which shows David Rockefeller bulldozing his way across Manhattan, in a vehicle adorned with the logo of what was then the family bank, Chase.

The reign of the planning cabal dated at least as far back as the city’s first zoning scheme in 1916, but it really got going with the RPA’s 1929 blueprint, which Bob wrote up in an essay called “Planning New York.” As Fitch put it, the essence of the 1929 plan was the division of the region into Slab City—the high-rises of Manhattan—and Spread City, the suburbs that surround the city center. The guiding idea was to concentrate high-end activities in the city center—finance and other fancy service businesses that could afford high rents—and move the noxious, low-rent stuff out to Jersey.

The reign of the planning cabal dated at least as far back as the city’s first zoning scheme in 1916, but it really got going with the RPA’s 1929 blueprint, which Bob wrote up in an essay called “Planning New York.” As Fitch put it, the essence of the 1929 plan was the division of the region into Slab City—the high-rises of Manhattan—and Spread City, the suburbs that surround the city center. The guiding idea was to concentrate high-end activities in the city center—finance and other fancy service businesses that could afford high rents—and move the noxious, low-rent stuff out to Jersey.

Their vision, with some bumps along the way (like the Great Depression, to start with) has largely been realized. I should say that Bob’s analysis has plenty of critics, who prefer “natural” economic forces as an explanation for the loss of manufacturing (and the port, which big real estate saw as a waste of a waterfront development opportunity). I’ll concede that Bob sometimes went too far when questioning the conventional wisdom. But there’s a lot to his argument, something we can see in the evolution of Long Island City over the last 20 years, as little industrial operations got replaced by high rises.

In any case, whether driven out by costs or David Rockefeller, the loss of manufacturing jobs was a blow both to the city’s working class and to its finances.

Some on the left point to the fact that New York City’s spending wasn’t out of line with other big cities. For basic functions—cops, fire, garbage, parks—it wasn’t. But that’s not the whole story. New York also spent wads on things other cities didn’t: hospitals and CUNY, notably. And while welfare spending, contrary to myth, wasn’t out of line with other cities. What was unusual was the state required the city to pay for lots of it (and for Medicaid); most other cities had their states pick up the tab.

Indulge me a moment of budget geekery here. First revenues and expenditures. On the current account, day-to-day spending on things like salaries, social spending, and office supplies, was pretty much in line with revenues until around 1970, when the budget went into serious deficit. But, like the TV ads used to say, that’s not all. The capital budget, which is supposedly where you account for spending on long-lived projects like roads and housing, was huge and growing. It makes sense to borrow for those things, given their longevity and economic returns, but the city was also hiding a lot of day-to-day spending in the capital budget.

The city’s short-term debt exploded. And since much of it was short-term, it had to be refinanced constantly. Unlike the federal government, which has near-limitless access to the credit markets, and which can, in a pinch, print money to cover any shortfall, a city or state has to balance its budget over the long term. What New York City was doing was unsustainable, and sooner or later things were going to break.

Yes, a lot of what the city was doing with that spending was good, but under our federal system, there are severe constraints on what a local jurisdiction can do. We can’t solve problems of structural poverty, deindustrialization—or now climate collapse—on our own. That requires federal policy, and in the 1970s, our political system was getting increasingly hostile to doing anything constructive.

the crisis

As 1974 turned into 1975, the banks made increasingly ominous noises about rolling over the city’s short-term debt. In April, the banks finally pulled the plug. The state forwarded the city some cash to get through the immediate crunch, but when the city tried to find some fresh money to borrow, the banks said no.

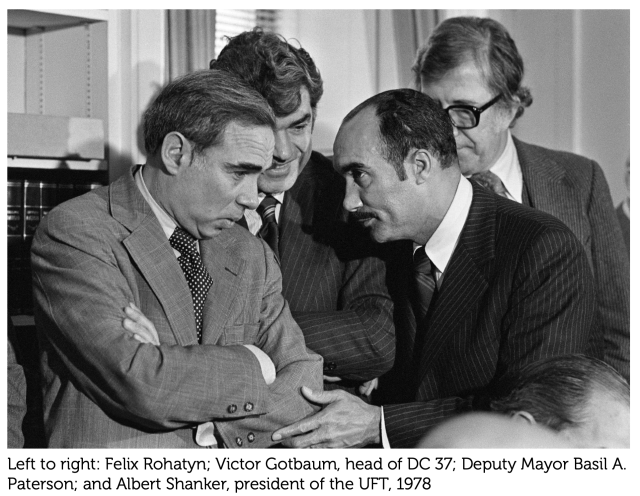

A commission appointed by Gov. Hugh Carey, who was nervous about the state’s own creditworthiness, recommended the creation of the Municipal Assistance Corporation, MAC, which would buy the city’s short-term paper by floating long-term bonds. But investors refused to buy the bonds. So, MAC, led by investment banker Felix Rohatyn, who was the proconsul of New York City in the second half of the 1970s, demanded and got wage freezes, layoffs, tuition at CUNY (which Felix admitted was of little fiscal impact, but necessary for the “shock value”), and a transit fare increase.

But the markets wanted more. So, in September Carey created an Emergency Financial Control Board (EFCB) to take over the city’s finances. Major revenue streams were diverted from the city to the EFCB, and it would release the money only if tight spending targets were met. All contracts, including with labor unions, would have to be approved by the EFCB.

That wasn’t quite enough either; in October the unions were persuaded to put hundreds of millions from their pension funds into MAC bonds. What’s sometimes fancifully called labor’s capital provided essential funding to the regime of austerity that would squeeze the city’s poor and working class for years to come.

That still wasn’t enough though. The Ford administration, advised by austerity partisans like William Simon, Donald Rumsfeld, and Alan Greenspan, refused the city any aid, prompting the Daily News’s famous headline. (While I was searching for a nice pic of the News’s front page, I discovered an earnest New York Times article helpfully pointing out that Ford never actual spoke those words.) They wanted outright class war on the labor unions and the city’s poor. Finally, in November, the feds agreed to make short-term loans to the city (at an interest rate a point above its own cost of funds—Washington likes to make money on bailouts). MAC finally realized its dream policy of selling long-term bonds to buy up the city’s short-term debt. The city’s elected government was largely set aside in favor of the bankers’ junta.

Between July 1974, when the city first started layoffs (almost a year before the crisis broke out) and November 1975 (when the first stage of the austerity program was completed), over a quarter of the city workforce was fired. Half the Latino workers lost their jobs, as did more than third of black workers. Over the next few years, one in six of the beds in municipal hospitals disappeared, and the welfare rolls were slashed. There was remarkably little organized opposition, unless you count the Spartacist League.

The unions complained at first. In one sensational incident, cop unions circulated an ominous flyer to tourists, warning them of the dangers posed by the shrinkage of the NYPD. They wanted their jobs back, but they weren’t showing much solidarity with other fired workers.

But the unions soon came around and even made common cause with the bankers through an organization called The Municipal Unions Financial Leadership Group, nicknamed MUFL (pronounced, appropriately enough, “muffle”). Crucial to organizing this effort was Jack Bigel (of whom more in a bit). The group produced research—prepared by the banker contingent but approved of by the unions—urging the city to turn away from poverty programs and focus instead on the needs of the better off. Rohatyn was impressed by the transformation in the labor leadership into a “totally realistic, responsible and cooperative” force. He and DC 37 leader Victor Gotbaum, who in his early days did a lot to organize some of the city’s most exploited—clerks, guards, cooks, cleaners, laundry workers—became the best of friends.

The unions’ dismal response to the austerity offensive is further proof of Sam Gindin’s argument that by their very nature they’re sectoral organizations with their own interests and not a force one should look to for political leadership. For that, you need a left party, half in and half out of organized labor, to provide historical, theoretical, and political perspective.

Obviously the bankers have the advantage in a debt crisis; they hold the key to the release of the next post-crisis round of finance. Anyone who wants to borrow again, and that includes nearly everyone, must go along. But that’s not their only advantage. The sources of their power were cited by Jac Friedgut of Citibank:

We [the banks] had two advantages [over the unions]…. One is that since we were dealing on our home turf in terms of finances, we knew basically what we were talking about, and we knew and had a better idea what it takes to reopen the market or sell this bond or that bond…. The second advantage is that we do have a…tight and firm discipline… [W]hen we spoke to the city or the unions we could speak as one voice…. Once a certain basic process has been established that’s an environment in which our intellectual leadership…can be tolerated or recognized…we’re able to get things effected.

It’s plain from Friedgut’s candid language that to counter this, one needs expertise, discipline, and the nerve and organization to challenge the “intellectual leadership” of such supremely self-interested parties. According to Gotbaum (in an interview with Bob Fitch, which Fitch relayed to me), the unions’ main expert at the time, Jack Bigel, didn’t understand the budgetary issues at all, and deferred to Rohatyn, whom he trusted to do the right thing. For the services rendered to municipal labor, the once-Communist Bigel was paid some $750,000 a year, enough to buy himself a posh Fifth Avenue duplex. Politically, the unions were weak, divided, self-protective, unimaginative, and with no political ties to ordinary New Yorkers. It’s easy to see why the bankers won.

There were aftershocks not worth going into, but the upshot was that over the next few years the city would balance its books in strictly orthodox terms. As its reward, the city returned to the bond market in March 1982, just as the national economy was about to shift from the punishing phase of neoliberalism, the high interest-rate austerity regime imposed by Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker, to the capitalist bacchanal of the Roaring Eighties. The stock market took off in August 1982, and the discourse shifted from urban decay to gentrification and, eventually, yuppie excess.

MAC would dissolve itself in 1985, but the EFCB lives on, though the Emergency was dropped from its name in 1978. It could reactivate itself if certain standards of financial orthodoxy were violated.

Felix

A little detour on Felix Rohatyn, a figure I was obsessed with for many years. He was quite the character. He’d later achieve some fame in liberal literary circles for writing soulful critiques of greed in the Reagan era, but in fact he and his mentor Andre Meyer pioneered a lot of the financial engineering schemes that the leading buyout artists of the 1980s would make famous.

As chair of MAC, Rohatyn would pioneer a lot of the austerity moves that would later be adopted nationwide—and, through the resolution of the Third World debt crisis of the 1980s, worldwide. Somehow he coasted above it all. As the late novelist/polemicist Michael Thomas told me at the time, Felix pounded the pulpit with one hand and endorsed checks with the other.

politics

What was at stake in New York was no mere bond market concern. The combination of political insurgency and rising spending to try to narcotize it alarmed the bourgeoisie, which generally felt it was losing control. This was a few years after the famous Powell memorandum, the 1971 call to arms for a besieged business class to organize in its own defense. And it was also a few years after the 1972 founding of the Business Roundtable, corporate America’s institutionalization of becoming a class for itself. As Felix Rohatyn said in a MAC meeting (a quote that Kim Phillips-Fein found in the archives), investors were avoiding New York paper because “the city’s way of life was disliked nationwide.”

To an increasingly politicized business class, its intellectuals, and its politicians, New York City was a perfect place to draw the line. In a 1976 New York Times op-ed, L.D. Solomon, then publisher of New York Affairs, wrote:

Whether or not the promises…of the 1960’s can be rolled back…without violent social upheaval is being tested in New York City…. If New York is able to offer reduced social services without civil disorder, it will prove that it can be done in the most difficult environment in the nation.

Thankfully, Solomon concluded, “the poor have a great capacity for hardship.”

Some planners viewed the crisis as a great opportunity, none more fervently and odiously than Roger Starr. Emerging out of the Yale/OSS aristocracy of World War II, Starr was first involved in the nonprofit branch of the real estate planning machinery. In the 1960s, Starr guided the Rockefeller-aligned Pratt Institute into what Forrest Hylton called “a new, post-liberal phase that would not only deny the extension of the New Deal and postwar achievements of New York’s white working class to blacks and Puerto Ricans, but roll it back altogether.” Northeast Brooklyn was their site for experimental urban renewal.

Beame then appointed Starr as his housing director. While director, Starr gave a speech outlining a strategy of planned shrinkage—cut services to the poor in the hope they’d move away. Of course, many planners thought that, but Starr’s indiscretion was say it openly. Here’s a sample at its bluntest:

Stop Puerto Ricans and the rural blacks from living in the city…. Our urban system is based on the theory of taking the peasant and turning him into an industrial worker. Now there are no industrial jobs. Why not keep him a peasant? Better a thriving city of five million than a Calcutta of seven million.

Those words got him fired from his city job, but then hired as an opinion writer for the Times, where he toiled for 15 years. An editor there recalled him as “exceptionally well tailored and always courtly.”

aftermath

Beame ran for re-election in 1977, but the fiscal crisis and a brutal SEC report on his role in it doomed his candidacy. Ed Koch, Greenwich Village reformer turned austerity partisan won. His mayoralty, though characterized by some stupendous episodes of corruption, consolidated the new austerity regime. In place of Beame, who found that regime deeply painful (though that regime had rendered him largely vestigial as a political force), came an enthusiastic partisan of the fiscal crackdown. He was happy to play the game of race-baiting. Poverty, which had been rising into the crisis, rose further in the Koch years, and homelessness became a mass phenomenon.

A transit strike in 1980, the first since Quill’s in 1966, was crushed. Attempts by plucky New Yorkers to walk to work were celebrated by the mayor and the media. Public opinion had moved heavily against the workers, and austerity consciousness had become hegemonic.

Austerity passed L.D. Solomon’s political test. There was no social explosion in the most difficult environment in the US, and the experiment was repeated in much of the rest of the world in the 1980s.

This was also the time, God save us, when Donald Trump became a celebrity. Trump’s rise to riches was lubricated by his father’s intimacy with the Brooklyn Democratic machine, notably future mayor Abe Beame and future governor Hugh Carey. These connections helped him get a 40-year tax break on his first major project, the renovation of the old Commodore Hotel next to Grand Central, that, in the words of Charles Bagli in the New York Times, “cost New York City $360 million to date [2016] in forgiven, or uncollected, taxes, with four years still to run, on a property that cost only $120 million to build in 1980.” Here are some of the principals celebrating this deal.

That would set the tone for economic development policy for decades to come: subsidies to luxury development given to capitalists who didn’t need them.

For many in the city, the fiscal crisis was a time of ruin and trash-lined streets. But one must acknowledge that while the crisis days were a time of misery for many, low rents were good for cultural production. Punk and hip-hop emerged out of it, and poets and painters could almost afford to live in Manhattan. It would be nice if we could get the low rents back without everything else going to shit.

But at the top of the ladder things started getting nice. After a decade of miserable performances, the financial markets were sparkling again by 1982. The shower of financier money began transforming the city’s physical and social infrastructure. The day of the yuppie was dawning.

principal sources

Charles Brecher and Raymond Horton, Power Failure (Oxford University Press, 1993)

Edward Gramlich, “The New York City Fiscal Crisis: What Happened and What is to be Done?” (American Economic Review, May 1976)

Eric Lichten, Class, Power, and Austerity (Praeger, 1986)

Kim Moody, From Welfare State to Real Estate (New Press, 2007)

Charles Morris, The Cost of Good Intentions (W.W. Norton, 1980)

Kim Phillips-Fein, Fear City (Metropolitan Books, 2018)

Michael Reagan, Capital City: New York in Fiscal Crisis, 1966-1978 (dissertation)

William Tabb, “The NYC Fiscal Crisis”

Economic stats from Bureau of Labor Statistics (employment), Gramlich (budget), and Morris (debt)

on Monday, March 18, at LaGuardia Community College in Long Island City, Queens. Kelley, a distinguished professor of history at UCLA, is calling his talk “From the Waterfront to the Sea: Working Class Democracy and the Question of Palestine.” I’ll be doing the intro.

More info here.

on Monday, March 18, at LaGuardia Community College in Long Island City, Queens. Kelley, a distinguished professor of history at UCLA, is calling his talk “From the Waterfront to the Sea: Working Class Democracy and the Question of Palestine.” I’ll be doing the intro.

More info here.

The reign of the planning cabal dated at least as far back as the city’s first zoning scheme in 1916, but it really got going with the RPA’s 1929 blueprint, which Bob wrote up in an essay called “

The reign of the planning cabal dated at least as far back as the city’s first zoning scheme in 1916, but it really got going with the RPA’s 1929 blueprint, which Bob wrote up in an essay called “